If your family is driving you crazy at Christmas, spare a thought for those whose travel plans have been disrupted by the drone incident at Gatwick Airport. Here are the numbers at the time of writing this…

Over 1,000 flights cancelled

Airport shut down three times over three days

140,000 passengers stranded

Here at PS Programmes Towers, we travel a lot for business, and a few years back got caught up in the fallout of Eyjafjallajökull, the eruption that did for air travel what it just did to our spellcheck. But we’re not just seeing ourselves bedding down for the night on the shiny floor of the North Terminal; we chair aviation conferences / summits and write crisis communications and contingency plans for the aviation industry. So, our interest is more professional than pure sympathy.

The problem?

‘I am surprised, frankly, that more drones have not been used to do bad things already… If people want to do bad with something they will.’ So says Dr Stephen Prior, a qualified drone pilot and lecturer in unmanned vehicles at the University of Southampton in the Daily Express.

Given that many of us are still required to take off our shoes in airports thanks to the failed shoe bombing in 2001 you could argue that the air industry is better at massive over reaction after an issue, and less good at seeing the trouble coming. And it’s not as if there weren’t warnings: here’s a piece from 2016 by Security Futurist and risk consultant, Simon Moores and if Gatwick don’t read blogs, they might’ve done something after it happened last year.

The problem is twofold. Firstly, the technology is new, and people get a drone for a few hundred pounds that they start using without checking the Civil Aviation Authority’s guidelines first. People didn’t used to think it was irresponsible to smoke indoors or get in the car after a few drinks, and now we know better. Before this week, you could argue, maybe people just didn’t know better.

The second half of the problem is that given the low cost and high disruption, the threshold to causing an incident is one that can be crossed easily – if you’re so minded.

One or the other was bound to happen, and we’re not going to speculate on whether this incident was mistake or malign. The Pilots Union, BALPA released this statement at the beginning of December, which is either prescient or underlies that last week’s incident was bound to happen sooner or later.

The reaction?

Arguably, the reaction of Gatwick Airport was pretty solid: Gatwick’s chief operating officer Chris Woodroofe was present on the media with a clear message, and didn’t repeat the mistake of BA boss Alex Cruz who went on the news in a hi-vis jacket, not normal attire for the IT department that caused disruption on that occasion.

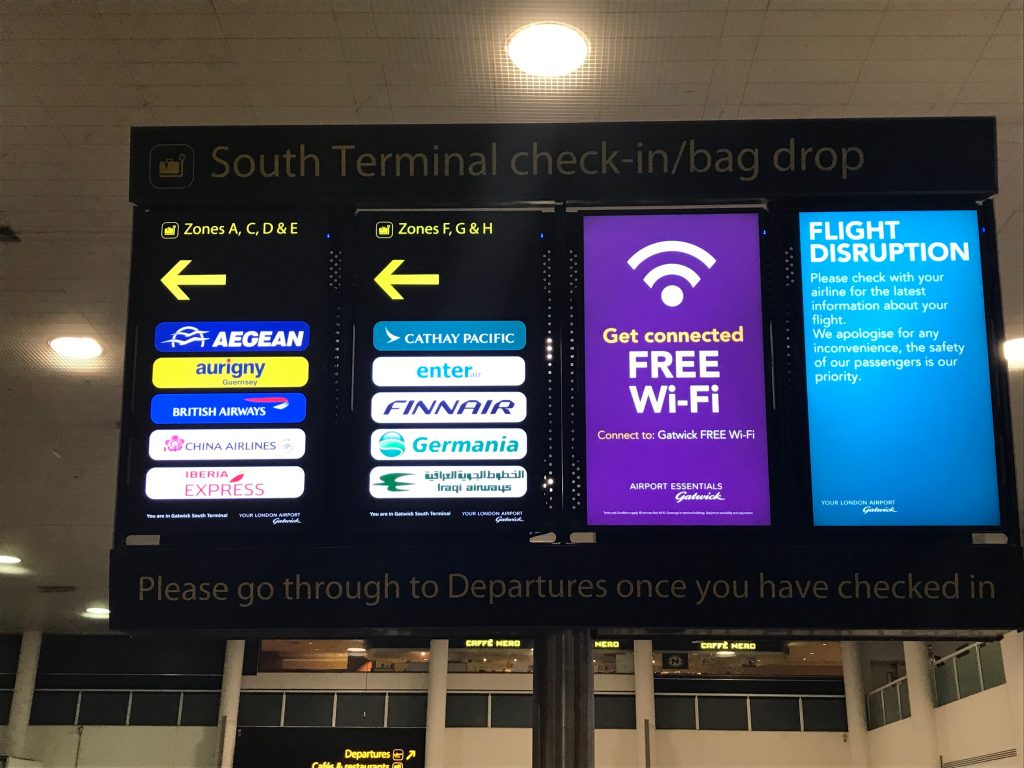

There was also good information distributed through social media. PS Programmes would like to pretend that we downed tools and dispatched a correspondent to the scene of the incident; in reality, one of us had a hire car booked and needed to get to Gatwick to pick it up. The status of the runways was an ongoing story, and the updates were frequent. We weren’t flying, but if we had been, a view could’ve been taken long before boarding the Gatwick Express. We’ve banged the drum before about the need for information to be freely available – and that means having a device to read it on. Free Wi-Fi is nice (so long as it’s easy to join), but after a few hours, it’s also important to have a way of charging your device.

Most of us accept that incidents happen, and the proof of a company’s quality is in the reaction. At Gatwick, warnings were ignored, and chaos ensued. But the blame isn’t squarely on the airport’s shoulders here. Sussex Police admitted it took several hours to mobilise resources, and said lessons have been learnt, but if a contingency plan had been put in place for a drone attack, then this would have saved wasted hours of staff running around looking like headless turkeys.

Steve Barry, Sussex Police Assistant Chief Constable, said it took ‘hours rather than days’ to request extra measures, but added: ‘Coordinating that, deploying that, getting it set up at Gatwick has taken some time, but we’ve learnt from that.’ Coordination is the key word here: a failure to anticipate the problem left those in charge in the police and at Gatwick acting on the fly – and however well they did, a plan and a drill would’ve made for a better outcome.

Secretary of State for Transport, Chris Grayling has come under fire: with less than 100 days left before the UK is scheduled to leave the EU, his lack of action this year – despite being told of the threat posed by drones – feeds into the narrative of a government in chaos. According to PoliticsHome, further legislation on drone use was due for publication in the spring, but delayed when civil servants moved to work on Brexit instead.

The insurance industry is also measuring their response: airlines say they are not obliged to pay out as the situation was outside their control. The Civil Aviation Authority considers this event to be an ‘extraordinary circumstance’ and ‘in such circumstances airlines are not obliged to pay financial compensation to passengers affected by the disruption.’

Travel insurers will have to make a choice between payouts or reputation. But they might argue that the Government itself should step up and compensate passengers, as their lack of action has been a contributory factor. The canny insurer (or airline) might make payouts to passengers, reaping the good PR while they reclaim the money off the government, but we wouldn’t hold our breath for this as an outcome.

Clearly the drone rules need to be beefed up. Listen to the pilots – the PPU are arguing for the owning of drones to be a regulated, licensed and registered practice. The PPU call the increase in incidents ‘exponential’ and a major incident like this is only going to make the problem worse, whether through idiot copy cats or deliberate and coordinated terrorist acts.

Simon Moores, mentioned earlier, also advocates that airports spend some of their huge security budgets on ‘drone rifles’ which, ‘pointed in the direction of an intruding drone threat simply disable it, causing it to land on its autopilot. End of story.’ If one of these had been in place following the last drone incident at Gatwick, it really would’ve been the end of this story.

As for the hero of the hour – we can’t decide if it’s more like Wall-E or Johnny 5. Whichever, maybe the time is right for it to take up a permanent position at the end of all of Britain’s runways.

Christmas bonus: how to deal with difficult family at Christmas?

We also interview people for a living, and professional detachment goes with the territory. But it’s more difficult when it’s a member of your own family saying something you don’t agree with – and saying it in the worst way at the worst time. So next time someone says something like: ‘This country needs a Donald Trump,’ here’s your cut out and keep (or slip into a cracker) guide to diffusing the situation.

1. Check your status: there’s a pecking order, and if you’re low on it, you’re going to be riled. The conflict you are feeling comes from someone who has more power saying something you disagree with. Think about it: toddlers say stupid stuff all the time, but when they do it, it’s cute. We want our leaders to know better.

2. Questions are your friend. Don’t say, ‘You’re wrong.’ Do say: ‘Why do you think that?’

3. One of the most powerful ways to calm down a conflict is to get people to see things from another perspective. ‘What would it take to change your mind?’ is a question that leaves only two options – be reasonable or thump the table and say ‘nothing!’ If the latter, save your breath, help yourself to more gravy and emerge as the better person by volunteering to wash up.

This article appears on Nadine Dereza’s website as well as PS Programmes.