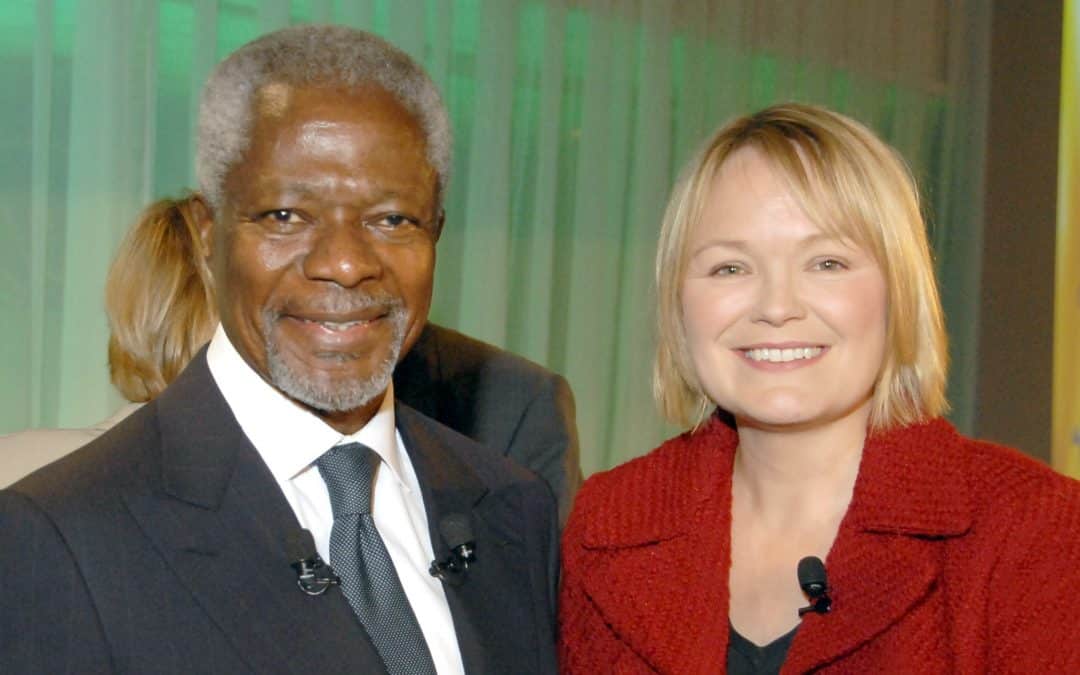

Recently, the world lost Kofi Annan, the former United Nations Secretary-General. I along with many others was saddened to hear the news of Kofi Annan’s death and felt extremely lucky to have met the great man – the ultimate diplomat. I interviewed him on a couple of occasions and was struck by his careful judgment and his strong moral conviction.

Kofi was a Ghanaian diplomat whose tenure in office marked a period in which the UN faced scandals of corruption and failed endeavour – yet emerged with credibility and respect. But these were not, ultimately, the lasting achievements of Annan.

When a young Kofi Annan walked into his first job at the World Health Organisation as a budget director in 1962, he was taking a major step along the path to what will be his legacy as an instrumental figure in the fight against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Africa.

His approach – compromise – laid him open to criticism, but like all diplomats, he put up with the showy onslaught in the opinion pages while the lives of the unseen were made a little easier. The balance between public policy and private enterprise is captured in his neat sentence from a report, WE the PEOPLES: The role of the United Nations in the 21st century (2000), calling on member states to ‘put people at the centre of everything we do. No calling is more noble, and no responsibility greater, than that of enabling men, women and children, in cities and villages around the world, to make their lives better.’

Annan himself was a gifted student with a background in economics and international relations, a period of his life which saw Ghana gain independence from the British, while he travelled to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the States to study management.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS – UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé describes Kofi Annan as a shining light, a rabble-rouser, a trouble shooter and a change-maker, an African at heart, but a global citizen, symbolising the best of humanity.

At the turn of the century, AIDS denialism was at its peak. Mr Annan helped to break it. ‘More people have died of AIDS in the past year in Africa than in all the wars on the continent. AIDS is a major crisis for the continent, governments have got to do something. We must end the conspiracy of silence, the shame over this issue,’ he said.

Under his leadership, in 2000 the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 1308, identifying AIDS as a threat to global security. In 2001, the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS was held—the first-ever meeting of world leaders on a health issue at the United Nations.

His leadership was not free of scandal: Annan was head of UN peacekeeping at the time when genocides were perpetrated in Rwanda and the former Republic of Yugoslavia, and he was in charge of the UN during the oil-for-food scandal in Iraq. But for all this his legacy – battling poverty, HIV, and climate change – set the UN on course for its ambitious sustainable development goals.

The Nobel Peace Prize, awarded jointly to Annan and the UN in 2001, was in recognition of the revitalised work of the organisation, prioritisation of human rights, and his commitment to the fight against the spread of HIV.

In retirement, Annan remained active until quite recently. Former British PM Gordon Brown writes: ‘I remember attending, at his invitation, a meeting of the Kofi Annan Foundation in Geneva and discovering how in his retirement, he was advising, in one way or another, a half-dozen countries in Asia, one or two in Latin America, and the majority of countries of Africa on human rights, elections, or poverty alleviation. For that reason, no single assessment can do justice to the breadth and depth of the successes of a leader who brought the UN’s decision-making out of smoke-filled rooms and into the 21st century.’

The endlessly quotable Annan accepted the UNAIDS Leadership Award in 2016 with the following words: ‘The fight is not over. We must continue the struggle and wake up each morning ready to fight and fight again, until we win.’ For those of us who know that tenacity trumps talent and consistency is the magic that makes real change stick, they are words to inspire today’s leaders to take up the baton just as he has let it go.

Kofi Annan, the first African to hold the office of secretary general, died with his work unfinished, but the world in a far better place than it would’ve been without him.

I’ll leave you with these inspiring words:

‘Education is, quite simply, peace-building by another name. It is the most effective form of defence spending there is.’ Kofi Annan

‘We don’t have to wait to act. The action must be now. You will come across people who think we should start tomorrow. Even for those who believe action should begin tomorrow, remind them tomorrow begins now, tomorrow begins today, so let’s all move forward.’ Kofi Annan

This article appears on Nadine Dereza’s website as well as PS Programmes.