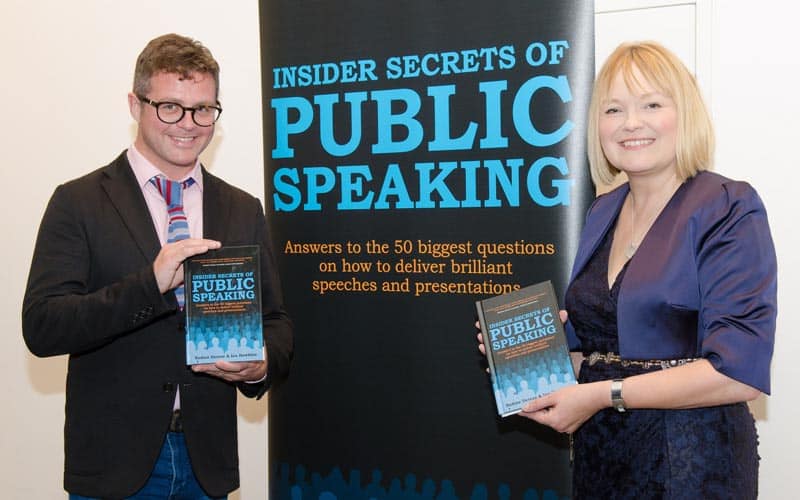

To celebrate the first birthday of our book, Insider Secrets of Public Speaking we are looking again at the core advice we’ve given in the light of our time spent presenting, hosting, speaking, coaching, and sitting in audiences watching other people on stage in the past year. This week: AUTHORITY.

Authority is a tricky one, and the one that we always worry will be misinterpreted. For the avoidance of all doubt, ‘authority’ is not battering your audience into submission, a heavy-handed know-it-all attitude, or the prompt removal of dissenters. Authority is about conveying two things in your speech or presentation:

1. Being in charge of the material

In many ways, this is the easy thing to get right simply by making sure you’ve done your homework. Time and again, we have noticed that speakers are so much better when they leave the script behind and directly address the audience, even if their spoken sentences are not as beautifully formed as the ones written on paper. Key facts and figures can live on a card or PowerPoint as a reference, but audiences aren’t usually there to watch someone regurgitate some numbers they have memorised: they are there to hear what the numbers mean.

Being in charge of the material means old-fashioned preparation: if you’re making a controversial point, ask a colleague or friend to debate with you beforehand. Do you believe in what you are saying? If you don’t, why should the audience? You have a choice in how you fill your time on stage, so take responsibility for what you are saying.

Although we are encroaching on the business of ‘authenticity’ – which is our subject next time – all three of our Golden Principles dovetail together.

2. Being in charge of the room

Audiences do not like ambiguity, and they don’t like not knowing what they are doing – so as the speaker, you must deliver clear directions (spoken or otherwise). When you speak, you have the spotlight, the platform and the microphone. In other words, you have the power, and with power comes responsibility. We think that this is really the core of people’s anxieties about speaking in public; once you accept this responsibility, you have come a long way towards turning the worst of your nerves into energy and focus for your performance.

A lot of the mistakes that people make in public speaking are to do with the discomfort they feel about being in charge of the room: apologising for nervousness, claiming not to have prepared anything (which is a massive insult to the people who are waiting to listen to you), reaching for the joke that is unrelated to what you’re talking about in the hope that it will buy you some audience sympathy… the list goes on. The audience has given you the authority to speak before you’ve even started, and so anything said to undermine this is giving precisely the sort of mixed message that audiences dislike.

Audiences, in the main, want you to do well. If you walk on believing this, you will unconsciously convey this message back to the audience. The same is true of the opposite: if you’re frightened of an audience, they will pick up on it, and begin to wonder what it is you’re trying to hide. Being on stage is like facing down a wild animal, first show no fear. Sometimes this is tough, but no tougher than being a tiger’s lunch.

A complete lack of humility, however, is difficult for people to swallow. The answer? Manners. Having good manners on stage is the balance that you strike with being in charge. Thanking people for their contribution and remembering to say ‘please’ when you ask for a show of hands are obvious indications of good manners. The mindset that we always use is to imagine that the room in which we are speaking is (albeit temporarily) our home, and that the audience are our personal guests. Guests expect their hosts to call the shots, lay the ground rules, and take responsibility for showing them a good time.

In conclusion.

So having authority on stage comes from the old-fashioned principles of stagecraft. The established actors’ habit of wiping your nose and checking your flies before you go on stage is a tip we can all use, remembering that it sits on top of a solid foundation of preparation. So long as you know your stuff and can adopt the principles of being a good host, having authority on stage can make speaking in public less nerve-wracking and more enjoyable. And speakers who enjoy themselves are the most engaging of all.

We’ll be looking at our other final Golden Principle, Authenticity, next time. Meanwhile, the essential reference book for anyone who needs to stand in front of an audience to speak is still available at Amazon.

This article appears on PS Programmes as well as this website.

Nadine Dereza is the co-author of the best selling Insider Secrets of Public Speaking.